MATRIX CITY, Ultrecht, 2010

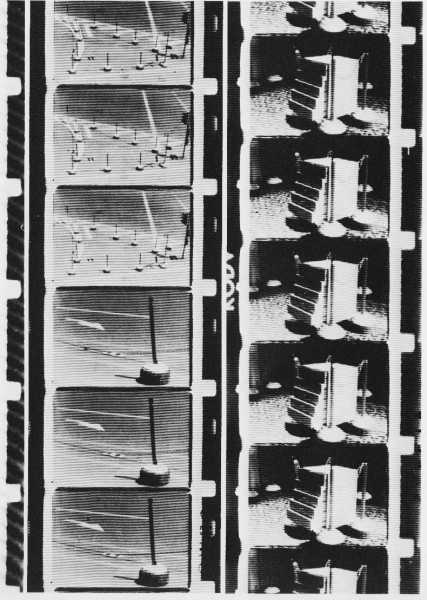

Ugo La Pietra, film stills, “Real Virtual” 1972

Ugo La Pietra, film stills, “Real Virtual” 1972

The following essay was originally published in “Matrix City” edited by Piet Vollard for the Exhibition Matrix City produced by Impakt Festival, 13-17 October 2010. curators: Stealth unlimited (Ana Dzokic, Marc Neelen) and Kristian Lukic./ Ultrecht

the metropolitan dreams of Ugo La Pietra/ Peter Lang

In one of Ugo La Pietra’s most memorable performance projects, staged in Milan in 1979, the architect-designer used half a dozen concrete moveable street bollards strung together with a loose chain, to cordon off an area on a busy city street where he arranged a bed for him to sleep in. La Pietra’s intent was to toy with simple everyday street furniture in an attempt to confuse the public’s perceptions on domesticity and civic space. As La Pietra observed in a recent interview, he wanted to construct new social-urban relationships “without any conditioning” making direct connections between an individual and the city and the city and the individual.

Though he acted for the most part on his own, he often collaborated with a broad community of critics, artists, designers, architects and urban designers. Part of the generation born in 1938, Ugo la Pietra finished his studies in 1964 at the Milan Politechnico, together with a number of notable classmates, including Renzo Piano. Like many in this period, he pursued his hand in painting, becoming in 1962 one of the founding members of “Gruppo del Cenobio” a short-lived artist collective named after the gallery where they collectively exhibited their work. They considered themselves part of Lucio Fontana’s circle, the Italian minimalist known for his provocative acts of canvas slicing.

By the time of the late sixties, however, Ugo La Pietra had become a prominent exponent in the Italian Radical design movement. And the most consistent expressive medium underlying Ugo la Pietra’s work was his use of multi-media documentation to develop his urban research and experimental postulations. Using photography, film, and later video, La Pietra explored Milan’s peripheries and quotidian street settings carefully registering common everyday uses, taking specific note of the most minor transformations made by the city’s anonymous designers. Then La Pietra would set out to disentangle them, through a careful process of analysis and de-codification. The Milanese architect- designer sought out rather unusual means to “re-appropriate” the city that he hoped would build, little by little, a virtual environment linked to the city’s active street life. A world that would be totally re-wired, an urban communications network that might well have anticipated today’s all pervasive internet.

Complimenting his urban research, Ugo La Pietra’s constructed an impressive network of contacts through his prodigious work as editor and publisher. In particular, he edited during the early seventies the magazine “In” which has since acquired almost cult status among those seeking out rare essays and projects by some of the most noted cutting-edge critics and designers from around the world. He also has a knack for curating, pulling together complexly structured exhibitions like “Spazio Reale-Spazio Virtuale: lo spazio audiovisivo” (Real Space-Virtual Space: the audiovisual space). Ugo La Pietra was involved in the Milan based collective Fabrica di Communicazioini (Communications Factory) and helped pull together, in 1973, one of the most spectacular short-lived collectives that immediately represented the who’s who of the Italian design scene—“Global Tools.” Oddly this assembly of later day Italian Radicals, that included the likes of Sotsass, Superstudio, Archizoom, 9999, UFO, Gianni Pettena, and other giants of the day, played a decisive role in auspicating the coming of the eighties Italian post-modernism.

Conceived as a sort of anti-school of Radical design, the Global Tools encounters took place just about the time when experimentation in conceptual design had passed its peak. By 1973, the architectural design world would begin to rediscover the more reputedly coherent values of strictly regulated formalist ideology, in what would be the equivalent of a return of the ancien regime. In fact many of the former “Radical” practitioners traversed this moment of crisis by adapting their skills to this new retro-trend, taking their designs into more stylistically mannerist frontiers. Ugo La Pietra, however, continued to keep to his urban conceptual practice, though the crafts undercurrent guiding the Global Tools school would certainly mark La Pietra’s later work.

It could be argued that La Pietra bridged the transitional seventies with his filmmaking. He made a number of films, from 35 mm shorts to documentary features. “La Grande occasione,” (The Great occasion) his earliest (15’ 35 mm BW film, produced by Abet Print-1972), was awarded the First Prize at the International Festival at Nancy in 1975. The film played on the untapped potential within the Milan Triennale building’s sprawling empty spaces. La Pietra also produced in 1979 Spazio Reale o Spazio Virtuale? (Real Space or Virtual Space?) (20’, 16 mm color film, production Milan Triennale). Rendered in documentary format, this film is a treatise on Milan’s deep urban culture teeming with local creative inventions.

Ugo La Pietra’s 1979 feature length documentary was tied to a much larger project connected to the XVI edition of the Milan Triennale, where he was brought in to develop one of the five themed sections in the exhibition. La Pietra had been appointed curator of this section by a distinguished commission, whose members included Gillo Dorfles and Umberto Eco. For “Lo spazio audiovisivo”, (Audiovisual space) the commissioners’ goal was to understand the multiple aspects of “the ‘space’ produced by the television screen, (space) ‘inside’ the television screen, as well as the ‘space’ promoted, solicited and conditioned outside of the screen itself.” (Virtuale Reale 5). La Pietra exploited this opportunity to tie together a number of open projects he had been working on over the decade, mostly exploring the dialectical relationship between the very real contexts of the city, and what lurked in the virtual world beyond.

While groups like Superstudio and Archizoom were formulating ways to derail contemporary society, through explicit attacks on the growing culture of conformism and consumption, La Pietra kept his focus glued to the local phenomenon of a rapidly expanding Milan. La Pietra gravitated around Milan’s extensive and unregulated un-planned, urban periphery, where he observed and photographed and later filmed small –scale individual interventions he found emerging in these areas. These became part of his broader survey on “minor” urban interventions, actions he would refer to as “Gradi della libertá” (Degrees of freedom). La Pietra suggested that through these contexts one could find the codes to unlock the repression around us.

“The places where we live are continuously imposed on us. In reality the space in which we operate can only exist as a mental model that is continuously modified through experience. It is necessary to find the form that is born out of our experiences instead of by imposed schemes.” (Ugo La Pietra “Instructions for the use of the city” Edizioni Associazione Culturale Plana,1978, republished in XVI Triennale di Milano, “Spazio Reale-Spazio Virtuale: lo spazio audiovisivo” Catalogue, Milan, Marsilio, 1979) 68

But La Pietra also sought out other urban contexts that might further his quest for “un-balancing” the living environment. He investigated the city centers, where he pointed his camera on very local manifestations of urban creativity, made largely by anonymous authors. Here his focus was primarily on storefronts, and much of what takes place at street level and on the sidewalks. These studies would also fuel alternative creative processes, which La Pietra split into different didactic themes: “Abitare è essere ovunque a casa propria” (living is being everywhere in one’s own home), Attrezzatrue per la collettività, (Equipment for the collective), Istruzioni per l’uso della città (instructions for using the city), Come disegnare la pianta della tua città (how to draw a plan of your city).

Each of these tactics represent steps towards what La Pietra identifies as the “re-appropriation” of the city, something he sees as similar to what native American Indians do when they give a kind of spiritual identity to a territory, a “sensorial value” to the landscape. In these next series of projects, which la Pietra called

Gradi della libertá (Levels o Freedom), La Pietra would attempt through a series of multi-medial tactics to subvert normal every day urban customs, creating social exchange mechanisms —on one hand through the designing of audio-visual technologies that would undermine typical barriers between inside and outside, domestic and public, and on the other a sort of urban de-codification, mapping, tracing,

As curator of “Lo Spazio Audiovisivo”, La Pietra asked Alberto Farassino to edit a section on international film, which included numerous Lumiere brothers turn of the century BW shorts, in a tribute to cinema’s conquest of urban space, as well as films by Michael Snow, Chris Welsby, and Clements Klopfenstein.

The re-appropriation of the city, 35mm BW 1977-78 produced for the George Pompidou Center, gives, according to Ugo La Pietra, “the poor results of an analysis for the discovery of the degrees of freedom that still exist on the inside of the urban system; they are the desperate and dis-organic attempts of a society that no longer can find reasons for what it does, for why it does what it does, or where it does it.” (Virtuale-Reale 68).

The significance of Ugo la Pietra’s work lies precisely in his capacity to seek out and document the kind of urban contexts in transition that suggest to him new strategies for creative urban intervention. La Pietra’s documentation serves to delineate an operative urban dimension where he can critically develop radically new experimental tactics… that back in the late sixties were explicit challenges to the existential condition of the modern city. But despite all the promises technology has offered in these last decades, Ugo La Pietra has not become that much more optimistic about the state of contemporary society. As La Pietra recently remarked: Today with the increase in technological tools it cannot be said that there is a major exchange between public and private spaces even if the marketplace of leisure time (like happy hour) encourages an even greater presence of people in urban spaces. The culture of today moves only great masses of people: concerts, blockbuster exhibitions… There still lacks, just like back in the seventies, places to “make culture.” (interview with PTL-). A meaningful call to get back to the basics, to get back out on the street and go for a spin.